The “Crisis” of Modernity

By fatherstephenWhat do you call a Christian whose mind is so constructed that belief in God is almost impossible?

Answer: a modern man.

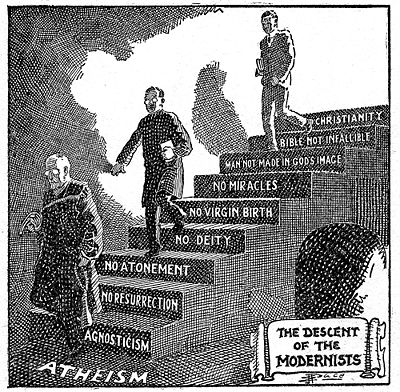

I occasionally make allusions to the crisis of modernity (in one form or another), as in a recent post in which I made reference to Florovsky’s term, the tragedy of Western Christianity. The crisis is not financial, though financial stumbles do reveal some of the cultural weakness within modernity. In many countries, it appears that very little is required to fill the streets with violent protest (though often the protest is itself without clear guidance or purpose).

The tragedy of Western Christianity is often shared by Eastern Christianity: that tragedy is the failure of the Church. I certainly believe Christ’s words that the “gates of hell” would not prevail against His Church. Despite its tragic failures, the Church has not disappeared (for thoughts on the historical problems within the Eastern Church, I reference an article by Met. Hilarion Alfeyev).

Much of Christian practice today has fallen into the individualism of modernity. The Christian life as a common life, lived only in the context of Christ's Body, the Church, is, for many, a concept that has little content beyond a sense of camaraderie with other Christians. Such an appropriation of Christianity renders the faith as simply one of many modern “life-style choices.” It is therefore not surprising that many “life-styles” that are traditionally rejected by the Scriptures are easily embraced within a Christianity that exists only as a set of “choices.”

The earliest Christians understood the true nature of the Church and did so in the context of a hostile, pagan culture. Modern Christians, even those that perceive the Church properly in its fullness as the Body of Christ, do so in a very strange society – a secular world that is “post-Christian” rather than simply pagan and hostile.

The “post-Christian” aspects of our culture make belief in Christ, as traditionally given by the fathers and the Church in its fullness, nearly impossible. To say that Christianity is “a way of life” is not the same thing as saying that Christianity is “a life-style choice.” Many modern Christians would be hard put to explain the difference.

Answer: a life-style choice is a set of actions based on decisions of an individual. A way of life (in its true meaning) refers to the fact that true union with Christ is the only means of true existence – all else is death or a movement towards non-existence.

In the post-Christian world, institutions have become ephemeral, based, at best, on the raw, coercive power they possess and can threaten to wield. That a pope could bring the Holy Roman Emperor (Henry IV) to his knees in the snow is now a tale of things past (and was not much of a tale at the time). Christians speak, issue statements to various governmental bodies, usually to no avail. The Church is not as strong as an opinion poll.

To approach Christianity as a “way of life” is to reject the Post-Christian world itself – to recognize the emptiness of secularism – and to set one’s life on a path that has no particular public standing in the world in which we live. To recognize Christ as the very source of our existence and well-being is to place nothing ahead of Him, or in competition with Him. It is to recognize that our true life is constituted by love of God, love of neighbor, and love of enemy. Everything else is subsidiary and of less significance. It is to place our life under the judgement of the End of all Things, rather than any other time or place.

The world which we now call the “modern” is simply one of many cultural arrangements that people have used for their daily intercourse. There is nothing inherently good or true in its constitution, nothing which demands our loyalty. Though “God” has been assigned a place within the secular order, such a place is not occupied by God, but only things which “stand” for God, and therefore are modern idols. A real God, is the end of all that secularism professes.

The crisis of our present world order is that it has no particular relationship with the God Who Is. It has established itself as superior to all else and the judge of the utility of all things. As such, it can have no true God.

To reject modernity and secularism sets a Christian on a path of conflict and difficulty. It requires that we see modernity for what it is (simply another human construct) and secularism for what it is (another human effort to relegate God to a relative station). It is a path marked by tension and struggle and much misunderstanding. But this is the struggle of our time, the crisis and tragedy which belong to our age.

May we have the wisdom to know our own age, and to know the true God in the midst of all things and to discern His voice from all of the delusions which seductively call to us.

22 hours ago

1 comment:

Good gravy -- enough of this romanticization of the medieval!

Medieval European society was just as subjectivist, relativist, and classist as "modern" society. Feudal Europe was never the marshmallow cloud Xanadu fetish that trad-ritualists have erected. 90% of the feudal European population never traveled more than five miles from their rude huts. Their entire slave lifes (yes, they were slaves, not ruddy and jolly "serfs") were razor-edge subsistence struggles.

The violence towards Jews, ostracization of "lepers", and implicit treatment of the slaves as mere implements hardly reflect the commonweal and congregational amity of the New Testament. The intellectual stratification of society through the concentration of literacy in the monastic and courtly spheres created an ethic and morality sometimes even at odds with both the rude necessities of the slaves and "orthodox" Christian doctrine.

The "relativism" (i.e. atomization of society) since the Enlightenment has brought about great advances in literacy and expression. Hate on David Hume all you want, but his affirmation of intellectual autonomy has brought us even to the Internet age.

As I oft repeat, we Catholics are responsible for liturgy and its implications. Idealization of any liturgical, theological, or exegetical point in Christian history contradicts ethical responsibilities. Leave the medieval infatuation with the Society for Creative Anachronism.

Post a Comment